New York Times Lincoln Essay Contest

© Richard Wightman Fox 2015

To celebrate Lincoln’s hundredth birthday in 1909, the Times put on an essay contest for the children of the Greater New York Area. Other urban papers, including the Philadelphia Ledger and the Cleveland Press, organized Lincoln competitions too, though none could rival the size of the Times endeavor.

Drawing on a city population of four and a half million, about three times that of Philadelphia (and nine times that of Cleveland), the Times attracted almost 10,000 qualifying submissions, many from New Jersey, Connecticut, and other towns in New York. All of the handwritten papers—capped at 500 words-- arrived with a teacher’s note certifying that the essay had been written “without outside help.”

“WINNERS OF THE LINCOLN COMPETITION MEDALS, CERTIFICATES, CASH PRIZES,” ran the seven-column headline on Page One of the “Magazine Section” on February 28, 1909. One thousand children had won silver Tiffany medals featuring the bust of Lincoln, and the top 100 were also given five-dollar gold pieces.

The Magazine printed the top ten essays, in facsimile form to show off the neatness and penmanship of the best writers. Four of the ten came from pre-teens, including one nine-year-old. For the Times, these youngsters proved irresistible. Their innocent directness of expression called to mind the mythic simplicity of Lincoln

The Times received such an overwhelming number of entries because the New York City school system jumped on board. Teachers were encouraged to assign the seven-part biography of Lincoln published in the paper in early February, the work of Frederick Trevor Hill, author of the recent book Lincoln the Lawyer. They helped their pupils grasp what the Times meant by an “original” response to Hill’s account. A dry summary would not suffice. Students had to seize the central points of Hill’s biography and make them their own.

“Lincoln was not a heaven born genius—merely a plain man who was honest, sincere, and upright,” wrote Hill. He learned growing up that strong “character” would get him through failure and disappointment. Any young person in any era, the Times urged, could adopt Lincoln as a model.

Their teachers promoted the contest, but the lure of a shiny medal fired the children’s ambition. Letters poured into the Times office from young hopefuls and their parents, explaining how badly they wanted to win.

One father thought he’d help his fourteen-year-old daughter’s chances by sending in an additional poem she’d written urging equal time for George Washington:

It’s Lincoln, Lincoln, Lincoln

Just cause he’s a hundred years old,

O’ course he deserves every bit of his praise,

And maybe I am kind o’ bold

To say that there’s some one better,

An’ tho’ I’m only one

I’m goin’ ter stick up for the father

Of this country, George Washington.

The Times cautioned youngsters not to expect special treatment for extra material of this kind. But the fourteen-year-old did get her medal.

Diminutive Alexandra Kliatshco, a Russian immigrant, and the nine-year-old winner of a silver medal and a five-dollar gold piece, became the paper’s prime symbol of equal opportunity. Alexandra had arrived in America from Russia only three years before, knowing no English. She had thrived at P. S. 177 in Manhattan, and she produced an elegant Lincoln piece. Her father, a physician on Henry Street, told the Times she had excelled at memorizing Russian poetry from the time she was three years old.

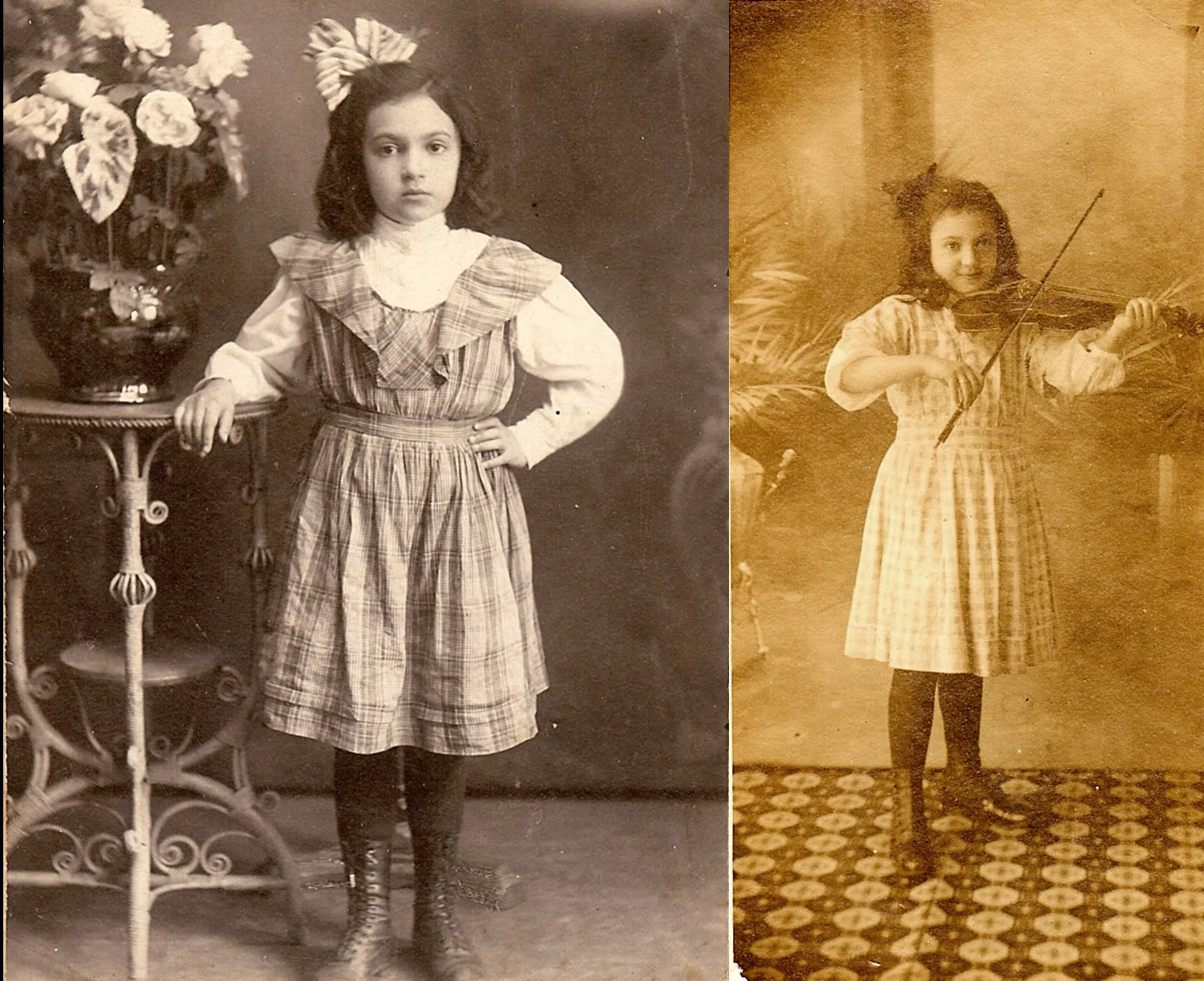

Anna Kliatshco, the nine-year-old Times contestant, and the eleven-year-old violinist.

Credit: Courtesy Julie Stern

“I am a little foreign girl, and I have been here only a short time,” her essay began, “but when I read about Lincoln, I thought that I might grow up a great woman as Lincoln was a great man.” And it ended: “We cannot forget the love he bore us and he died leaving the world better than it was. I hope that I can be like Lincoln, unselfish, kind, thoughtful and modest.”

A 1998 profile in the Times noted that her prediction had proven accurate. Alexandra Kliatshco Werner had graduated from Teachers College in 1922 and taught art for 40 years at Jane Addams Vocational School in the Bronx. She loved impressionist paintings, classical music, and Alfred Hitchcock, and she had tried her hand at poetry. Alexandra had not held on to her Lincoln medal, preferring to make a gift of it to her father, who died in 1928.

A regular contributor over the decades to the Times “Neediest Cases” fund, Mrs. Werner—an eloquent Lincoln essayist of 1909-- died in 1997 at the age of 97.